Uncategorized

ACT- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

By Mat Richardson

My Journey with ACT started 10 years ago when I was suffering with chronic pain (A link to a blog on my pain and depression), I was lost and couldn’t see a way out. I used a similar framework to ACT to get me out of trouble and didn’t even know this is what I was doing. My shoulder pain had been present for over a year and I went down the traditional biomedical pathway of diagnosis, treatment & resolution of pain. If you can’t enter this pathway, or you do and don’t get resolution, what then? For me I spiraled into depression and pain and was becoming fused to my undesired self. Adopting experiential avoidance as a coping strategy, I started participating and engaging in less activities. I was losing flexibility in life, had no clarity on my values or who I was and all I could see was the sick and undesired self. At this time, I was very fused to my thoughts and feelings, my mental health and pain spiraled downward.

Then the turning point: one day I woke up and thought if I died at that moment, I wouldn’t have cared. I picked up the phone and called my doctor to get help for my depression, she put me on antidepressants and at this time one of my patients introduced me to mindfulness. Both ingredients were key for me getting out of my hole. Mindfulness taught me self-compassion, that thoughts were not fact and that I could create space and not automatically respond. I became less reactive and more reflective, I was able to sit with sensations and feelings without reacting and bring a curious mind to them and stopped the struggle with them. If someone had used the word acceptance back then I might have punched them, but using a willingness to let pain be and focus on what you value, was more acceptable to me. I looked at my life and started clarifying what I valued, what made Mat, Mat. Gradually I started to see who I really was and started to get flexibility in life. Over a few months the pain went away, and my mental health improved. Without realizing it I had done an ACT intervention on my self, but I didn’t know what ACT was until many years later.

ACT aims to increase Psychological Flexibility, “to maximise human potential for a rich and meaningful life, while effectively handling the pain the inevitabley goes with it” (Harris, 2019). Psychological flexibility has 6 core processes with 4 of them directly from Mindfulness.

- Contact with the present moment

- Self As Context

- Defusion

- Acceptance

- Committed Action

- Values

The first part of my story I was doing the opposite of ACT, I was becoming psychologically inflexible. I was caught in a trap of trying to get rid of pain and couldn’t live life until it was gone: trying to find the silver bullet and my life was on hold (Bunzil B. W., 2013). I had become psychologically inflexible- not connecting with the present moment, remoteness from values, unworkable action, fusion with undesired self and experiential avoidance (Harris, 2019).

A little exercise if you are a Practitioner: what components of psychological inflexibility may relate to the Yellow flags, that predict a patient with a poor outcome and may lead to pain related disability?

2 years ago when I attended a workshop run by Alison Sim and Dr Bronnie Lennox Thompson exploring how ACT can be used to help people with persistent pain and I realized this is essentially what I did many years before. The processes involved with ACT tickled my biases, as I had already been practicing Mindfulness for many years. ACT is a third wave Psychological therapy that was developed mid 80’s by Steven Hayes. Now I am not saying for manual therapists to become Psychologists, but what I am saying is there are trains of thought, processes and techniques we could use in the clinic that could be very helpful when working with people in chronic pain. We are not digging into trauma or diagnosing psychological conditions as this is outside of a lot of our scope of practice. I believe we need to know about these different approaches so we can work with counsellors or Psychologist to give the patient consistent messages, hence having a wide referral network is invaluable.

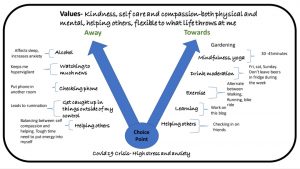

The best person to practice ACT on, is yourself, so during the second wave of Covid 19 and stage four lockdown, I drew up a choice point, I could see all the triggers for my stress and anxiety were present: I couldn’t work, money getting tight, home schooling kids and uncertainty with what will happen next. On the bottom I placed the situation: stage 4 lockdown where I was unable to work, high stress and anxiety. I then drew 2 arrows one towards the person I want to be and one away from the person I wanted to be, guided by my values. I did some work with values clarifications and wrote them on the top. Functional contextualism is a key idea that flows through ACT, where a behavior is neither good or bad. Rather, “what effect does this behavior have in a particular context”(Harris, 2019) and whether it moves you towards (workable) or away (unworkable) to the person you want to be (values). You will notice drinking alcohol appears on both sides of the arrows. When I am not stressed, two or three beers tends to relax me (towards), but if I am anxious or stressed, two or three beers can amplify these responses and can affect the quality of my sleep (away). With watching the news I needed to watch enough to know what was going on (towards), but not checking in all the time or watching the news throughout the day because this would trigger my stress and anxiety (away). Mindfulness appears strongly in my “towards me” arrow, as it allows me to defuse from the stressors. This allows me to make space for them and not attempt to push them away (acceptance). I filled my day with lots of towards moves but there were still days where I was down or frustrated and this is alright!! I just didn’t allow myself to get caught up in the struggle, and brought acceptance to them and controlled what I could control.

Image- Adaption of the choice point (Russ Harris)

ACT has a large clinical framework, full of process and tools to use. I haven’t gone into depth in this section of the blog, as I only wanted to get across the essence of ACT and tickle your curiosity to explore further. One aspect of ACT I love is: you are 2 humans that have experiences, share and work collaboratively together to get you out of a predicament whilst building more skills and coping strategies for the future. You can choose workable actions towards the person you want to be and build in a range of coping strategies for the future. I need to be watchful as personal experience has given me a huge confirmation bias towards these types of therapies and interventions and need to keep checking in on myself.

Reference

Harris. (2019). ACT made simple second edition. New Harbinger Publications.

For a full reference list see blog on Pain, Protective Responses and Relationships

Mindfulness- The most important coping strategy I used during the Lockdown

The most important coping strategy I used during the lockdowns was mindfulness. I was lucky enough to have been practicing the skills and teaching for the last 10 years. During the lockdown all the triggers for my depression, stress and anxiety were there, uncertainty about the future with money, work and the sense of hopelessness. I made Mindfulness an integral part of my day, to cope with the stress of living under stage 4 restrictions. The formal practice is the training, and this gets infused through my day. When rumination about life would come up and they did, I was able to defuse and step back, creating space from the thoughts and becoming less caught up and reactive to the thoughts. Bringing acceptance around life and unfairness of the being shut down was challenging, but was important for decreasing the struggle. Below is a section out of my last blog on my journey through mindfulness.

The most important coping strategy I used during the lockdowns was mindfulness. I was lucky enough to have been practicing the skills and teaching for the last 10 years. During the lockdown all the triggers for my depression, stress and anxiety were there, uncertainty about the future with money, work and the sense of hopelessness. I made Mindfulness an integral part of my day, to cope with the stress of living under stage 4 restrictions. The formal practice is the training, and this gets infused through my day. When rumination about life would come up and they did, I was able to defuse and step back, creating space from the thoughts and becoming less caught up and reactive to the thoughts. Bringing acceptance around life and unfairness of the being shut down was challenging, but was important for decreasing the struggle. Below is a section out of my last blog on my journey through mindfulness.

Growing up in the Yarra Valley was a fun time for me, after school I would grab my fishing rod and walk down to the river, sitting there for hours watching the tip of my rod for slightest movement. Without realizing, this was my first taste of mindfulness; I was training my powers of focused attention. My dad explained to me once that fishing is not about catching the fish, it’s about being out in nature and enjoying what is around you, the platypus, birds, frogs and watching the fish jump out of the water. It was a lesson on not being too goal focused because if you went fishing to catch fish and your enjoyment depended on it, then you would come back disappointed a lot, but if you savor in the journey and the experience, then every fishing trip will be valued.

Mindfulness has been around for Millenia in many different forms and by many different religions in many different forms. In modern times it was Jon Kabat Zinn who introduced it to the current generation, with his MBSR (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) course that was first run at the University of Massachusetts in 1979. The course was originally to help treat chronic pain, but over the years has evolved to help people with depression, anxiety, and many different mental health conditions. Mindfulness is moment to moment nonjudgmental awareness. Mindfulness is not just meditation, but a way of living life being present, open, curious, and kind. Meditation is useful practice via which you can train yourself in mindfulness to infuse this moment to moment non-judgmental awareness throughout your life and daily activities. Just reading about mindfulness won’t change you, but it’s the practice of it that is important.

Jon Kabat Zinn published a book based on his 8-week course, 30 years ago, titled Full Catastrophe Living. Jon got the title of his book from the movie Zorba the Greek, and embodies a lot of what the book teaches. “appreciation for the richness of life and the inevitability of all its dilemmas, sorrows, tragedies, and ironies. His way is to dance in the gale of the full catastrophe, to celebrate life, laugh with it and at himself, even in the face of personal failure and defeat”. (Zinn, 2004)

In my late 20’s I was struggling with life and I couldn’t see a way out, when I look back, I had stopped doing my valued occupations like fishing and cricket, the importance of these activities didn’t become clear to me until many years later. During this time one of my long-term patients saw that I was struggling and mentioned that I should go to a mindfulness courses (MBSR- Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) she was running. I enquired about the price, but I could not afford it at the time. She then offered me a lowered price that I could afford. I am forever grateful to this wonderful woman for sending me on this new path of discovery and is a practice that I utilize to this day, every day. Here is a link to a blog I created on my story of Pain, depression and becoming who I am.

When I started the Mindfulness course, I was blank slate and didn’t have a lot of preexisting knowledge about mindfulness. In Explain Pain terms using the sandcastle metaphor, I had a few loose grains of knowledge that were not tightly held or influential about Mindfulness. I knew it had something to do about mediation and reducing stress, but I hadn’t explored it any further. I fully embraced this course because I wanted to get better and I did the 2 hours of practice per day. Over the next 8 weeks I started to see a change in the way I perceived and interacted with the world and I could start to see a way forward.

The most important thing I learnt was we are not trying to push perceptions or thoughts away but bringing them closer, sitting with them and giving them space. When we have bodily experiences breathing into them and becoming curious, feeling the size shape and where it is, not adding any more to the story and trying to defuse our automatic responses. When a lot of people start out, they might get caught in the trap of pseudo acceptance, where they are doing the mindfulness to get the pain or stress to go away, but this is just another avoidance strategy and is not true acceptance. “Acceptance is opening up to our inner experience and allowing them as they are, regardless of whether they are pleasant or painful” (Harris, 2019). What you will find is when you stop the struggle with experience and just be with it, curious and nonjudgmental that over time you may give the experience less power. In regard to a patient and their pain, we are changing the patient’s relationship to their pain, where it becomes less of a problem and they stop the struggle with it.

What about the evidence? While there have been thousands of studies on mindfulness, the quality of evidence varies from poor to good. A Meta-analysis on Mindfulness released in 2017 (Lara Hilton, 2017), only showed small improvements on zero to ten reported pain scale, but there was significant changes in depression and physical health related quality of life. I think this is where the true value in mindfulness is. We are not trying to get rid of pain but change the relationship to the pain to make pain less of a problem and decrease the disability associated with that same pain. Stopping the struggle with pain and giving it space just to be and using your energy towards what you love and value.

People may look at me strange when I say the most important and hardest skill I have learnt in my life is mindfulness! But, keeping up a regular practice, constantly challenging your skills around nonjudgmental moment to moment awareness is hard work. It not a passive process but an extremely active process where you are continually bringing your attention back to what you are focusing on. The goal is to notice your mind wondering, rather than stop it wondering and be kind and compassionate as you bring your awareness back to the present. The key ingredient is: every time your mind wanders, don’t be too disheartened or angry but count this as a win and show yourself compassion because when you become aware that your mind has wondered and you bring it back, this is where the true power of mindfulness is, to bring you back to the present.

Pain, Protective Responses & Relationships

By Mathew Richardson

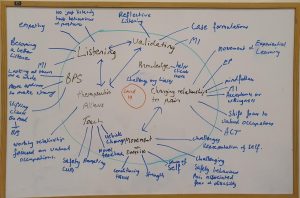

A few years ago, I was sitting in a café having lunch with Amy a local Clinical Counsellor. Within our conversation, she made the comment that a lot of what I do with my patients is change the relationship they have with their pain. I started explaining in fancy jargon (to make myself sound smart) about Explain Pain and conceptual change theory, then I stopped and realized how right she was. In doing some self-reflection in the days that followed, I started to see a lot of what I do in the clinic is about relationships. During the Covid-19 crisis I decided to draw a bubble of what I believed was important in my clinical practice. From this, I unpacked all the skills I use to achieve them

Changing and building relationships made up a big part of what I drew on the whiteboard. The term relationship can be used in many different contexts and we use many different skills to create this. Over the years, I have learnt more and more about the importance of connecting with people and how good communication skills are paramount in the clinic.

The bubble I wrote this year is vastly different from one that I would have done a decade ago, where I am sure I would have written soft tissue treatment, dry needling and many of the technique-based interventions we were taught at university. It is important to reflect on your clinical practice and to keep evolving with science and best practice. I will be intrigued to revisit the white board and this series of blogs in 5-10 years’ time and explore how I have evolved over that period.

“If I am still working the same way in 6 months, then this is not good enough, it means I have not learnt” (O’Sullivan, 2018)

The bubble also shows that I don’t just use one intervention, but rather, blend different interventions together depending on what is best for the individual patient. Chronic pain is complex; and you need a broad skill set to help a range of people with their unique pain experience in the context of the patients’ own lives. This emphasises the need for continued development of our knowledge and interpersonal skills, and the immense importance of understanding what other healthcare professions offer. Broadening our view allows us to appreciate the boundaries of our own practice and to offer the best path forward for each patient by utilising our professional network. We all love a bit of confirmation bias but to really challenge yourself and offer the best service possible, make it a priority to explore new ways of thinking. Along your journey, you may have to lose some clinical mileage and losing clinical mileage can hurt. Here is a link on a great blog by David Butler about clinical mileage. So, be kind to other practitioners on their journey and help to facilitate and guide others, rather than shooting them down. By working on our own knowledge, skills and awareness and realising we are part of a bigger picture within the healthcare system, we act to improve the group’s capacity to perform its role. These values and actions will go a long way to building useful and positive relationships and alliances in every aspect of professional practice.

In this blog we will explore some of the relationships in the clinic and the skills we can use to achieve a conceptual shift, to move you towards your valued activities and the life you want to live. These include: Initial interview (practitioner and patient), Explain Pain (Educational intervention), Mindfulness, ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) and Movement and Exercise. Do I use all these interventions by myself? No. I have a wide network of healthcare practitioners in the Hill’s, with different skill sets to assist me. We work together for what is best for the patient, but we need to know about these different interventions to make an appropriate referral. The major aspect I forgot to add in my bubble was networking with the local practitioners and building a community network (click on this link to see a blog on networking). We always need to be cautious of our scope of practice and not dig deeper into trauma or psychological conditions but have a referral network at hand to refer the client to a practitioner with skill sets in that area. So, enjoy my journey of exploring different interventions, to help people change their relationships with pain and bodily responses.

Initial Interview – Listen. No, REALLY listen.

As a practitioner, the most important and undervalued clinical skill, is the relationship between you and the patient. Really spending the time to connect with your patient and listen to their story and value this. A few months ago, a new patient came into the clinic and started telling me her complex and emotional story. I was able to extend her appointment and I sat and listened to her for 2 hours. In my early years in the clinic, I didn’t value listening enough and would have rushed to get the patient on the table and do what I believed was “treatment”. But now, I take the time to listen and build a relationship. Being a good listener is therapeutic in its own right.

“When you talk, you are only repeating what you already know. But if you listen, you may learn something new” (Dalai Lama)

As clinicians, the righting reflex is strong. We want to jump in as soon as we see something to correct or fix and becomes like a reflex response. In the initial interview, fight that righting reflex. When we start to correct or try to “fix” the patient, it may alter the story the client is telling you and thus, the way the clinician interprets the information. (Bronnie Thompson, 2018). Click on this link to see the brilliant Bronnie Lennox Thompson conduct an initial interview ..

“When we’re fully present with our clients, open to whatever emotional content arises, defused from our own judgments, and acting in line with our core therapeutic values connection, compassion, caring and helping, then we naturally facilitate a warm, kind, open, authentic relationship” (Harris, 2019)

During a talk I was giving last year at Osteostrong in Hawthorn, I was asked a question from a practitioner who was in the audience: “How do we get the patient thinking in more of Biopsychosocial way, instead of just expecting just the bio?” My response was that before the client has even entered your clinic it is important to set the scene, the patient may have seen many practitioners before you and most likely been conditioned to expect a more biomedical clinical encounter. The biopsychosocial model of care needs to be infused through your websites, blogs, advertising, and initial intake forms. If all your marketing and information is more biomedical, then when the patient get to the room and you suddenly start asking questions about beliefs, emotions, work, mood and stress, the client may look at you a bit confused and won’t give you the full story. My initial intake form has many questions from the Orebro and pain catastrophizing questionnaires, this allows me to gather information before they arrive and also shows the client that I am not just interested in the bio. Before the client has entered your clinic, we are planting seeds of change that we can cultivate in the clinic.

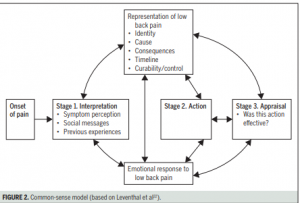

The next stage is the processors of validating and helping the patient make sense of why they are stuck. Validating the clients experience is important, it also shows that you have taken the time to listen. The skill of motivational interviewing (MI) will come in handy, elicit a rich story through the use of open questions, affirmations, reflective questions and summaries (Low, 2016) . At the end of an appointment last year a patient said to me: “no one has ever listened like you have”, this put a smile on my face because listening and validating are 2 skills I have been working hard on over the last few years. When a patient has left the room after the first appointment, I like to do a case formulation on the whiteboard. This allows me to put the vast array of information about the patient and their interpretations of this onto a whiteboard. I can then clinically reason the best ways to help move them move forward. Working with the patient over the next few sessions we can work together on developing a plan to get them back to what they love and value. The case formulation models I like to use are the Commonsense Model (Bunzil, 2017) and a modified Tim Sharp’s CBT Model (Thompson B. , 2018), but these are just 2 of a multitude of case formulation templates.

“Case formulations provide an ideographic depiction of the unique features of this person at this time, establishing a set hypothesis to explain the persons predicament” (Thompson B. L., 2019)

“A person will come in with a big box of jigsaw pieces and they have forgotten what the picture looks like, it is up to us to help the client put it together and help them make sense of where they are at” (O’Sullivan, 2018)

If appropriate, I will work through the case formulation on the whiteboard with the client on the second visit and discuss with the patient, the many different ways I can help with moving forward. This shows the patient that I have listened, and I am working with them to develop a personalized plan for them. If there is any information on the whiteboard that is incorrect, I am happy for the client to step in and clarify. I want to ensure aspects and inferences I have made of their story are correct. Case formulation will show the emergent and multifactorial nature of human experiences and how they interact, cultivating a shift the from a linear to a more biopsychosocial framework. We can then problem solve together and start to formulate a plan to get them out of their predicament (adapted Thompson 2019 & Bieling 2003).

I was sitting back at a workshop three years ago on the Psychological interventions into pain and the speaker asked us to turn to the person beside and speak for one minute about the positive attributes of one of our patients. The catch was, it had to be the client that when you see their name in your appointment book, you just sigh and feel drained before you have even seen them. I thought of one client in particular and I went to open my mouth and say something positive and nothing came out. I sat there in silence and was horrified that my judgements and relationship with this patient was stopping me from seeing the good. This was a good lesson for me to not just focus on the negative with patients but try and see the light. Now when I get stuck with a patient, I ask myself the question Do I see this person as a rainbow or a roadblock? Throughout the many weeks of working with your patients you will need to keep developing and working on the relationship.

Do I see this person as a rainbow or a roadblock? A rainbow is a unique and beautiful work of nature. Can we truly appreciate the gift granted of working at a deep level with our fellow human beings (Harris, 2019)

Invest more time in building a relationship with the patient and slow up the process during the initial interview. Listen, reflect, validate, and help them make sense, before formulating a plan. Before we embark on trying to change or implement change, we first need to listen with empathy, compassion and build a therapeutic alliance.

Listen, No REALLY Listen

Explain Pain- Pain Neuroscience Education

My journey with Explain Pain started in my second year of University in 2001, when I stumbled on the book by Adelaide Physiotherapist David Butler, Mobilisation of the Nervous System (Butler, Mobilsation of the nervous system , 1991). I loved the book and my young biomedical brain just ate it up. At that stage in my career I was still looking for a pain generator in the body or the tissue that was creating the pain, I left Uni in 2002 and started work in Tecoma the following year. In those early years when a patient came in in pain, I would stretch, massage, dry needle and strengthen and this worked very well for me for many years, but there was always a percentage of patients that I could not help. When I reflect, a lot of my thinking was flawed, and my patients were getting better through mechanisms I didn’t understand. Over the years I started to lose faith in what I was taught, then in 2012 a pivotal turning point happened in my career. I decided to google that bloke from Adelaide again to see if he had written anything else, I nearly fell off my chair when I realized I had missed a whole new world.

Reading Explain Pain for the first time many years ago, triggered a seismic shift in my understanding of the pain. The reconceptualisation from a more biomedical, linear understanding of pain, to a more biopsychosocial, emergent understanding of pain, made so much sense to me and opened up a whole new world of oppertunities to help my patients. Education can be just as powerful for our patients, Explain Pain utilises storytelling and metaphor to bridge the gap between what the patient knows and what they don’t; knowledge can have a powerful analgesic affect by decreasing the fear and threat value of pain. My understanding now is that we are not trying to replace preexisting knowledge but give the patient a greater repertoire on how to respond to their pain, challenging preexisting beliefs and shifting the probability gradients to networks that hold more helpful and accurate knowledge, thus hopefully having more influence over our behavior and responses. We don’t want to give the patient a superficial understanding of pain, but a deep learning that will affect their behavior. A lot of the time education alone won’t change a person, but it’s what they do with this knowledge that’s important and challenging embodied behaviors.

People come into the clinic with a wide array of misconceptions about their pain and some of these may be powerful enough to drive their pain. The misconceptions come from many sources including watching others, through experiential learning and a big one is from healthcare providers. A study in 2017 showed that 89% with pain, have a traditional biomedical view of pain. Patients believed that pain was due to the body being “broken” or something was “wrong” and indicated they learn this from health practitioners (Avemarie, oct 2018)(Setchell, 2017). One of the big misconceptions about pain is the relationship between pain and tissue damage. If you think every time you get pain that you are doing damage, then the commonsense approach is too avoid those activities. This can lead to cycle to avoidance, deconditioning of the tissues and as time goes on you may lose flexibility in life trying to protect yourself. They develop a narrower response profile to when there is a threat and you can become stuck. The good news is that Pain is more about need to protect than damage and our protective response will be more active when there are more threats either perceived or real around us. Education is one way that we can change our patient’s relationship by giving the person more ways to respond with more flexibility.

When I am doing a case formulation after the first one or two sessions, I will critically think of the best ways that we can get the patient out of their predicament. If an educational intervention would be helpful in the context of a wider treatment plan, then I will map out target concepts that are specific to the patient story and how I will get this across to the patient; looking at all the variables, my own and the patients. Personalising the target concepts to the patients context will help to maximise the learning and relationship change to movement, thoughts, beliefs and pain. Do I believe we need to give every patient a deep understanding of pain, well no. For some patients, just enough knowledge that pain doesn’t mean they are damaged can be enough and this shift in the relationship to their pain is enough and they are off. I have a wide array of stories and metaphors that I use and adapt for each patient. You will also have complex pain patients where you will slowly, over many years, start creating a conceptual shift in their understanding of pain and this can be an extremely slow process.

In 2015 Butler and Moseley released The Explain Pain Handbook: The Protectometer (Bulter, 2015). In this book they explore pain, depends on a balance between dangers and safeties in your world. The more dangers or threats around us the more our protective responses will be turned up, bringing us closer to pain and vice versa. What is a danger or a safety will vary depending on the patient’s experiences, knowledge and inferences they have made. Do I think this can be reconceptualized further? Yes, I have stopped using the terms DIMs and SIMs as a lot of clients think it’s a bit gimmicky and I now just use dangers and safeties. On the whole, I believe the protectometer is a very helpful tool and is a nice formula for patients to understand the value in prioritising things that bring them a sense of safety and trying to decrease their exposure to dangers, thus decreasing danger signalling in the body, reducing the need for protective responses like pain. Here is a link to a protectometer I did of my own experience of pain and depression from many years ago.

In the past allied health practitioners have been extremely poor at education, where in the Psychology world psychoeducation has been a part of their practice for decades. A study released in 2018 ( (Traeger, 2018) showed that two, one hour didactic lectures on pain education compared to active listening where no information was given with people with acute lower back pain, showed no significant difference between the 2 groups. In this study they compared education to something that I think is one of the most important skills we use in the clinic is active listening. This study shows that with acute injury, time is probably one of the biggest determinants on whether some will get better. The interesting part of the study was the secondary finding of decrease in disability and recurrence in the months after the study. This study was not powered enough to hang their hats on these secondary findings but does point to education having some very positive effects. You can’t just give the patient an information dump, you need to adapt every time you do an educational intervention, to suit the person that is in front of you. Even though this study did not go the way the researchers thought it would, it triggered more avenues to explore ways of conceptual change, that might be more effective (Moseley L. , 2020).

Lorimer Mosely, one of the researchers on this study, wrote two blogs explaining the study:

Butler and Moseley are great examples of clinicians and scientists that are evolving with the science and are constantly challenging and updating what they teach and how they deliver it. I am forever grateful to David Butler, Lorimer Moseley and the Noigroup for setting me on a new path many years ago and triggering a dramatic change in my clinical practice and my understanding around pain and human experience. Explain Pain skills are now infused through my entire clinical practice and is one way I work with the patient to create a shift in their relationship to their pain, but education is just one piece in a complex puzzle.

Mindfulness

Growing up in the Yarra Valley was a fun time for me, after school I would grab my fishing rod and walk down to the river, sitting there for hours watching the tip of my rod for slightest movement. Without realizing, this was my first taste of mindfulness; I was training my powers of focused attention. My dad explained to me once that fishing is not about catching the fish, it’s about being out in nature and enjoying what is around you, the platypus, birds, frogs and watching the fish jump out of the water. It was a lesson on not being too goal focused because if you went fishing to catch fish and your enjoyment depended on it, then you would come back disappointed a lot, but if you savor in the journey and the experience, then every fishing trip will be valued.

Mindfulness has been around for Millenia in many different forms and by many different religions in many different forms. In modern times it was Jon Kabat Zinn who introduced it to the current generation, with his MBSR (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) course that was first run at the University of Massachusetts in 1979. The course was originally to help treat chronic pain, but over the years has evolved to help people with depression, anxiety, and many different mental health conditions. Mindfulness is moment to moment nonjudgmental awareness. Mindfulness is not just meditation, but a way of living life being present, open, curious, and kind. Meditation is useful practice via which you can train yourself in mindfulness to infuse this moment to moment non-judgemental awareness throughout your life and daily activities. Just reading about mindfulness won’t change you, but it’s the practice of it that is important.

Jon Kabat Zinn published a book based on his 8-week course, 30 years ago, titled Full Catastrophe Living. Jon got the title of his book from the movie Zorba the Greek, and embodies a lot of what the book teaches. “appreciation for the richness of life and the inevitability of all its dilemmas, sorrows, tragedies, and ironies. His way is to dance in the gale of the full catastrophe, to celebrate life, laugh with it and at himself, even in the face of personal failure and defeat”. (Zinn, 2004)

In my late 20’s I was struggling with life and I couldn’t see a way out, when I look back, I had stopped doing my valued occupations like fishing and cricket, the importance of these activities didn’t become clear to me until many years later. During this time one of my long-term patients saw that I was struggling and mentioned that I should go to a mindfulness courses (MBSR- Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) she was running. I enquired about the price, but I could not afford it at the time. She then offered me a lowered price that I could afford. I am forever grateful to this wonderful woman for sending me on this new path of discovery and is a practice that I utilise to this day, every day. Here is a link to a blog I created on my story of Pain, depression and becoming who I am.

When I started the Mindfulness course, I was blank slate and didn’t have a lot of preexisting knowledge about mindfulness. In Explain Pain terms using the sandcastle metaphor, I had a few loose grains of knowledge that were not tightly held or influential about Mindfulness. I knew it had something to do about mediation and reducing stress, but I hadn’t explored it any further. I fully embraced this course because I wanted to get better and I did the 2 hours of practice per day. Over the next 8 weeks I started to see a change in the way I perceived and interacted with the world and I could start to see a way forward.

The most important thing I learnt was we are not trying to push perceptions or thoughts away but bringing them closer, sitting with them and giving them space. When we have bodily experiences breathing into them and becoming curious, feeling the size shape and where it is, not adding any more to the story and trying to defuse our automatic responses. When a lot of people start out, they might get caught in the trap of pseudo acceptance, where they are doing the mindfulness to get the pain or stress to go away, but this is just another avoidance strategy and is not true acceptance. “Acceptance is opening up to our inner experience and allowing them as they are, regardless of whether they are pleasent or painful” (Harris, 2019). What you will find is when you stop the struggle with experience and just be with it, curious and nonjudgmental that over time you may give the experience less power. In regard to a patient and their pain, we are changing the patient’s relationship to their pain, where it becomes less of a problem and they stop the struggle with it.

What about the evidence? While there have been thousands of studies on mindfulness, the quality of evidence varies from poor to good. A Meta-analysis on Mindfulness released in 2017 (Lara Hilton, 2017), only showed small improvements on zero to tenreported pain scale, but there was significant changes in depression and physical health related quality of life. I think this is where the true value in mindfulness is. We are not trying to get rid of pain but change the relationship to the pain to make pain less of a problem and decrease the disability associated with that same pain. Stopping the struggle with pain and giving it space just to be and using your energy towards what you love and value.

People may look at me strange when I say the most important and hardest skill I’ve learnt in my life is mindfulness! But, keeping up a regular practice, constantly challenging your skills around nonjudgmental moment to moment awareness is hard work. It not a passive process but an extremely active process where you are continually bringing your attention back to what you are focusing on. The goal is to notice your mind wondering, rather than stop it wondering and be kind and companssionate as you bring your awaeness back to the present. The key ingredient is: every time your mind wanders, don’t be too disheartened or angry but count this as a win and show yourself compassion because when you become aware that your mind has wondered and you bring it back, this is where the true power of mindfulness is, to bring you back to the present.

ACT- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

My Journey with ACT started 10 years ago when I was suffering with chronic pain (A link to a blog on my pain and depression), I was lost and couldn’t see a way out. I used a similar framework to ACT to get me out of trouble and didn’t even know this is what I was doing. My shoulder pain had been present for over a year and I went down the traditional biomedical pathway of diagnosis, treatment & resolution of pain. If you can’t enter this pathway, or you do and don’t get resolution, what then? For me I spiraled into depression and pain and was becoming fused to my undesired self. Adopting experiential avoidance as a coping strategy, I started participating and engaging in less activities. I was losing flexibility in life, had no clarity on my values or who I was and all I could see was the sick and undesired self. At this time, I was very fused to my thoughts and feelings, my mental health and pain spiraled downward.

Then the turning point: one day I woke up and thought if I died at that moment, I wouldn’t have cared. I picked up the phone and called my doctor to get help for my depression, she put me on antidepressants and at this time one of my patients introduced me to mindfulness. Both ingredients were key for me getting out of my hole. Mindfulness taught me self-compassion, that thoughts were not fact and that I could create space and not automatically respond. I became less reactive and more reflective, I was able to sit with sensations and feelings without reacting and bring a curious mind to them and stopped the struggle with them. If someone had used the word acceptance back then I might have punched them, but using a willingness to let pain be and focus on what you value, was more acceptable to me. I looked at my life and started clarifying what I valued, what made Mat, Mat. Gradually I started to see who I really was and started to get flexibility in life. Over a few months the pain went away, and my mental health improved. Without realizing it I had done an ACT intervention on my self, but I didn’t know what ACT was until many years later.

ACT aims to increase Psychological Flexibility, “to maximise human potential for a rich and meaningful life, while effectively handling the pain the inevitabley goes with it” (Harris, 2019). Psychological flexibility has 6 core processes with 4 of them directly from Mindfulness.

- Contact with the present moment

- Self As Context

- Defusion

- Acceptance

- Committed Action

- Values

The first part of my story I was doing the opposite of ACT, I was becoming psychologically inflexible. I was caught in a trap of trying to get rid of pain and couldn’t live life until it was gone: trying to find the silver bullet and my life was on hold (Bunzil B. W., 2013). I had become psychologically inflexible- not connecting with the present moment, remoteness from values, unworkable action, fusion with undesired self and experiential avoidance (Harris, 2019).

A little exercise if you are a Practitioner: what components of psychological inflexibility may relate to the Yellow flags, that predict a patient with a poor outcome and may lead to pain related disability?

2 years ago when I attended a workshop run by Alison Sim and Dr Bronnie Lennox Thompson exploring how ACT can be used to help people with persistent pain and I realized this is essentially what I did many years before. The processes involved with ACT tickled my biases, as I had already been practicing Mindfulness for many years. ACT is a third wave Psychological therapy that was developed mid 80’s by Steven Hayes. Now I am not saying for manual therapists to become Psychologists, but what I am saying is there are trains of thought, processes and techniques we could use in the clinic that could be very helpful when working with people in chronic pain. We are not digging into trauma or diagnosing psychological conditions as this is outside of a lot of our scope of practice. I believe we need to know about these different approaches so we can work with counsellors or Psychologist to give the patient consistent messages, hence having a wide referral network is invaluable.

The best person to practice ACT on, is yourself, so during the second wave of Covid 19 and stage four lockdown, I drew up a choice point, I could see all the triggers for my stress and anxiety were present: I couldn’t work, money getting tight, home schooling kids and uncertainty with what will happen next. On the bottom I placed the situation: stage 4 lockdown where I was unable to work, high stress and anxiety. I then drew 2 arrows one towards the person I want to be and one away from the person I wanted to be, guided by my values. I did some work with values clarifications and wrote them on the top. Functional contextualism is a key idea that flows through ACT, where a behavior is neither good or bad. Rather, “what effect does this behavior have in a particular context”(Harris, 2019) and whether it moves you towards (workable) or away (unworkable) to the person you want to be (values). You will notice drinking alcohol appears on both sides of the arrows. When I am not stressed, two or three beers tends to relax me (towards), but if I am anxious or stressed, two or three beers can amplify these responses and can affect the quality of my sleep (away). With watching the news I needed to watch enough to know what was going on (towards), but not checking in all the time or watching the news throughout the day because this would trigger my stress and anxiety (away). Mindfulness appears strongly in my “towards me” arrow, as it allows me to defuse from the stressors. This allows me to make space for them and not attempt to push them away (acceptance). I filled my day with lots of towards moves but there were still days where I was down or frustrated and this is alright!! I just didn’t allow myself to get caught up in the struggle, and brought acceptance to them and controlled what I could control.

Image- Adaption of the choice point (Russ Harris)

ACT has a large clinical framework, full of process and tools to use. I haven’t gone into depth in this section of the blog, as I only wanted to get across the essence of ACT and tickle your curiosity to explore further. One aspect of ACT I love is: you are 2 humans that have experiences, share and work collaboratively together to get you out of a predicament whilst building more skills and coping strategies for the future. You can choose workable actions towards the person you want to be and build in a range of coping strategies for the future. I need to be watchful as personal experience has given me a huge confirmation bias towards these types of therapies and interventions and need to keep checking in on myself.

Movement

Exercise has been the gold standard intervention for pain used by therapists for decades, but what does the research say? Unfortunately, it’s a bit all over the place: some meta-analysis support and some show only small changes in pain. A recent systemic review by Karlsson 2020 showed no important difference in pain or disability was evident when exercise therapy was compared to sham ultrasound (Karlsson, 2020). What this study showed me is that in the acute setting regression to the mean probably plays an important role, where time is probably the biggest factor for recovery. Do we throw the baby out with the bath water with exercise? Well, NO. I believe movement has so much to offer from challenging protective behaviours, how we interact with the world, conditioning and health of our bodies and the list goes on. The theme of this blog is to explore using movement as an educational tool, to change the bodies relationship to pain & movement and decrease disability associated with pain.

Back to my pain story again from 10 years ago: through experiential avoidance I was using my body less and less and was fearful of the meaning of my pain. I was developing a self-discrepancy (Kwok, 2016), where my past self the guy who was active playing sport, wood chopping and worked in physical jobs was now becoming my undesired self, weak and sick and I was creating my own hopelessness. They day I decided to start using my body again, in spite of my pain, this was the day I started to form a new self. Movement became a vehicle of change, where I was challenging my representations of who I was by doing valued occupations. In this time, I don’t think strength was a huge factor in the change in me, it was changing my relationship to who I was, that I was still strong and I could do what I loved and I was not broken.

A light bulb moment happened to me 2 years ago at the Explain Pain 3 conference. Professor Peter O’Sullivan did a live case study with Russel, a person who had suffered decades of pain and how it took him away from what he loved and the person he wanted be. Even though we were at an Explain Pain event that promotes educational interventions to help people with pain, Prof O’Sullivan educated and shifted the relationship for Russel around pain without explaining pain once through a didactic approach. The education came through exposing him to what her feared (bending over by flexing his spine) by altering the context by decreasing sympathetic arousal and relaxing the body. We eventually watched Russel bend over by flexing his spine with minimal pain. This even surprised Russel. This experiential learning through movement was a powerful moment for me and showed that education and conceptual change can come in many forms.

I had a client come in to see me a few months ago that was told by his clinician that he had a nerve entrapment of the sciatic nerve through the gluts. He was given neurodynamics gliding and tensioning exercises and based on being told that the nerve was trapped, he aggressively tensioned the nerve in an attempt to un-trap it. He did his exercises religiously and his symptoms got worse over many weeks to the point where he was scared to walk and was disabled by his pain. He came to see me in the clinic and testing showed that he had an extremely sensitised straight leg raise and altered by head flexion and extension. We did some Explain Pain- Pain and tissue damage rarely relate, the sensitive nervous system and that nerves don’t usually get trapped. In a seated position we did gentle neural gliding and touched the edges of his pain. Breathing and relaxing to decrease sympathetic arousal and gradually over 5 repetitions his pain reduced. We explained that certain positions and tensioning of the nerve was now being perceived as being dangerous and was contributing to his pain. Through graded exposure we are teaching the body that it is now safe to move through the range in that particular context. Movement became the learning tool and over the next few weeks the pain reduced. If we had done just an Explain Pain intervention it may have reduced his pain but combined together with challenging the embodied behaviour we saw a large reduction in pain and function improved.

During the Covid lockdown 2.0, I decided to take up yoga. I put on some tight yoga pants and started practicing. A lot of my patients think yoga is a about stretching to create a lasting change in the tissues and I am sure this occurs if you practice it for 6-12 months but if they push to hard to get the stretch or choose movements that are too challenging then this might increase protective responses. This is where some education combined with movement can be very powerful. I explain to them that yoga is a great way to challenge the protective responses of the body by gradually exposing you to postures and movements. Over the time the body gradually learns these positions are less dangerous and we can see a decrease in protective responses and you are able to move through a larger range. Done in a mindful and controlled way we will see nice feedback through the body and will also alter cortical representations in motor and sensory maps and representations of self. Yoga is a great example of a movement-based therapy that incorporates many facets of health. I am learning that a lot of what I have been doing in the clinic ove rthe years, has been done in Yoga for generations.

When giving movement-based strategies, really think about why and what you are trying to achieve? Too many therapists do it for strength without much thought regarding the many other ways movement can have its therapeutic effect. When giving movement-based strategies, become creative and collaborative and use the patients values-based activities to help problem solve ways of doing activities even if pain persists.

Conclusion

This blog has been about the importance of relationships in the clinic and how they can have an effect or buffer protective responses. I am hoping this blog has fueled a curiosity to explore different ways of thinking about what we do in the clinic and how we get the therapeutic effects. As a therapist this blog may have challenged the idea of trying to eradicate pain and instead getting the client moving in spite of pain. By decreasing the struggle with pain, by focusing on what they value, love and identifying the person they want to be, may enable pain to become less of a problem.

I started writing this blog during the first Covid 19 lockdown over 6 months ago. We’re now in the second wave and have been in stage four lockdown for many month and I have not been allowed to treat face to face in the clinic during this time. My relationship to being an Myotherapist is growing stronger and this time away is only fueling my passion for helping people on their journey to better health.

Special thanks to my editors Rachel Bentley, Janice Moore & Karen Lucas

References

Avemarie, L. (oct 2018). The communicative therapeutic effort in pain management. Paincloud research reveiw, 3.

Beiling, K. (2003). Is cognitive case formualtion science or science fiction. Clinical psychology, science and practice.

Bulter, M. (2015). The Explain Pain handbook, The Protectometer. Noigroup Publications.

Bunzil, B. W. (2013). Lives on hold. journal of clinical pain .

Bunzil, S. S. (2017). Making sense of low back pain and pain related fear. JOSPT.

Butler. (1991). Mobilsation of the nervous system . Churchhill and Livingston.

Butler. (2017). Clinical Mileage. Retrieved from Noigroup: https://noijam.com/2017/08/18/clinical-mileage/

Butler, C. (2017). Explain Pain . Melbourne: Noigroup.

Butler, M. (2003). Explain Pain . Noigroup publications.

Harris. (2019). ACT made simple second edition. New Harbinger Publications.

Islip, A. (2018). Think Better Counselling and training.

Karlsson, B. L. (2020). Effects of exercise therapy in patients with acute low back pain: a systemic review of systemic reveiws. systemic reviews.

Kwok, C. C. (2016). The self in pain: the role of psychological inflexibility in chronic pain adjustmen. Journal of behavioral Medicine.

Lara Hilton, M. S. (2017). Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annuls of behavioral medicine, 199-2013.

Low, M. (2016). A novel clinical framework: The use of dispositions in clinical. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice.

Moseley, B. (2017). Explain Pain Supercharged. Noigroup Publications.

Moseley, L. (2020, August 25th). Pain,Science and senibility. (B. Hilton, Interviewer) Retrieved from https://ptpodcast.com/pain-science-and-sensibility-episode-49-contemplating-possibilities-and-the-impermanence-of-pain

O’Sullivan, P. (2018). Explain Pain 3. Melbourne, MCG: Noigroup.

Setchell, C. F. (2017). Individuals explanation of their persistent or recurrent low back pain a cross secional survey. BMC, Nov 17:18(1):466.

Thompson, B. (2018, October). Initial interviewing. Retrieved from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VbXTlkqcNI&list=PLq2gNbAASX46nO-ddlSX6winhj6_w8nA4&index=20&t=229s

Thompson, B. L. (2019). Clinical reasoning in complex cases. Pain Cloud, 6-11.

Traeger, H. L. (2018). Effect of Intensive Patient Education vs Placebo Patient Education on Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama neurology .

Zinn, J. K. (2004). Full Catastrophe lviing. New York City : Delta trade paperbacks .

Remote learning, Working form home & Being kind to yourself

Remote learning, working from home and being kind to yourself

By Mathew Richardson

As the second lock down rolls on and with the threat of stage 4 restrictions, Melbournian’s are waiting anxiously to see if the stage 3 restrictions will decrease the spread of the virus. With remote learning #2 due to start next week, another layer of stress for parents, students and teachers is added to the mix. During remote learning #1, tears were commonplace in the clinic and I was flooded with parents trying to juggle home schooling, working from home, financial worries and a lot of their coping strategies had been taken away. Our lives revolve around routine and habits in order to make us more efficient, but now we are attempting to juggle many balls in the air at the same time and trying to make sense of new ways of being; and this is exhausting. Patients were coming in with severe, disabling pain and in high levels of distress. If we look at this pain as being less about tissue damage and more about the body’s evaluation of threat (either perceived or actual) then this makes sense (click on this link for a short video on sensitivity and protection). Our body has a bias towards protection and if we are surrounded by threats, we are far more likely to have protective responses like stress, pain and muscle spasm. This is our body doing its best to keep us safe and protected, but what was designed to keep us safe, can end up being the problem itself.

A common question I ask patient is: “Before Covid, what were normal ways that you look after yourself?”. People often answer: yoga, gym, catch up with friends, bowls, meditation etc. A big part of what I do in the clinic is try to find ways for the client to get back into what they value and love, as this can be a great way to buffer the stress and pain responses. The activity may not look exactly the same as before, but we will try and capture as many of the values you hold dear and make you feel a little bit like you again. Allowing time to look after yourself and giving yourself space is important and don’t feel guilty about it. For me, personally, during this time, I have tried to increase the coping strategies that move me towards who I want to be. These strategies include meditation, mindfulness, education, fishing (lock down #2), running and helping others whilst decreasing the coping strategies that move me away, like alcohol. During this time, find ways to include coping strategies that make you feel more like you again, re-gaining control and prioritizing your wellbeing.

As well as juggling life, a lot of us are trying to work from home and we have lost a lot of incidental movement like walking to the train station, going to the toilet, social interactions and all the other movement we would normally do in our workplaces. Thus, stressing the importance of more movement into your day at home including large holistic motions and not just little stretches. Whether it is dancing around the kitchen, yoga or a 5 min walk, I don’t really care as long as you are moving. Power it up, combine it with something you love like music or your garden (don’t forget to smell the roses). Our body loves motion as it keep our tissues healthy, puts nice feedback through our systems and gets us out of the postures we have been stuck in for hours. So, let’s try and replace the incidental movement we have lost from our workplaces by trying to include more of these movement strategies into the day… set a timer and just do it.

Practitioners over the years have put a lot of emphasis on ergonomics in your workspace, but this is just one piece in the puzzle. If your body is already stressed and edgy and ready to protect you, then yes, the ergonomics of your workstation can play a role with pain and stiffness. However, it is also important to look at the other things you can change too, like more movement strategies, stress reduction, working less hours, adding breaks whilst including things you do to make you feel more like yourself again. By doing this, you might find that the ergonomics matter a little bit less.

Be kind to yourself during this challenging time and use coping strategies that move you towards what you value and who you want to be. Don’t feel guilty and show yourself some self-compassion, because it’s important to prioritize and look after you, so you can look after others. (click on this link to see a short video by the brilliant Russ Harris on face covid)

Stay safe

References

Triple peaks model, Butler Moseley, Explain Pain sec ed, Noigroup publications, 2012

Networking for better healthcare- Inspire and build community

Networking for better healthcare

“Inspire and build community”

From the day I started working in Dandenong Ranges (“The Hills”) 18 years ago, I would go around to the clinics in the area to meet the health practitioners and build connections. Building relationships within my local community was important for growing and developing my business and to create a referral network my patients. 4 years ago, I decided to bring the practitioners in the hills together, to create a collaborative networking group for the best care of our patients. Imagine a world where you have different practitioners with different skills working together to help people on their journey to better health! My aim for the group was to develop a network of health care practitioners with different skills, so that we could:

- Give our patients the best care

- Support each other with the challenges of clinical practice

- Learn from and with each other

- Have a diverse range of talks to cover many different areas of health

All in a non-judgmental, fun, educational and caring environment.

When people come into our clinics do they just come in with just a sore shoulder or back? Well NO, they come in with all the complexities that make us humans. One practitioner won’t have all the skills to help a patient with all facets of their health. But when a network of practitioners bring their different skill sets and work together, we can give our patients the best quality of care, and get them onto the road to better health.

As practitioners we are working with people every day, but it can be a lonely job and you can feel isolated. A big part of the group is supporting and helping each other with the challenges of running a practice and with how life interacts with it. A lot of this is driven through my own personal experience many years ago where I myself felt isolated and I was struggling with life. Some of the talks have been aimed about self-care for the practitioner to make sure we have coping strategies to keep us at our best. The practitioners in the group have become close friends and people I can now rely on for support and for this I am very thankful.

I have chosen a wide range of topics to be covered during the talks because humans are emergent complex beings. To treat people effectively, we need a diverse and wide knowledge of health. Some of these topics are outside of our scope of practice, but I believe that to make an appropriate referral for a patient, you need to have a diverse knowledge base to draw upon to get them to someone how can help them further. A lot of practitioners say they use the Biopsychosocial model of care to make themselves sound smart. What this refers to is how health involves the complex and emergent interactions of the biological, psychological, and social elements of our life, and these cannot be separated. The Biopsychosocial model of care has been infused through the presentations (or talks?) to make sure the practitioners are seeing the whole human that is in front of them.

“One thing I realized a long time ago, is how anyone reasons is hugely dictated by what you plan to do- the more biased and limited your skills/ knowledge, the more blinkered and limited your reasoning is going to be” (Louis Gifford, 2014)

In The Hills we are lucky to have an amazing and caring group of practitioners that work together for what is best for the patient. Rest assured that if you are a person in need of help and you see one of these practitioners in the network you will get the best care or be referred to someone who can. During this emotional and stressful roller-coaster that is the Covid- 19 crisis, the support from the fellow local practitioners has been a great comfort to me and shows how much we care about each other and our well being.

We say a big thank you to the wonderful people that have given talks to our group over the past 4 years and a big thank you to the amazing practitioners we have in the Dandenong Ranges (“The Hills”).

4-week Mindfulness course- Michelle Johnson

Dementia- Suzanne Mcloughlin

Stress, Pain & neuroplasticity- Mat Richardson

Gut Health- Marika Rodenstein

Understanding Pain-Mat Richardson

Insights into grief- Karen Philippzig

Pelvic health- Liana Johnson

Self-care for health practitioners- Amy Islip

Breathing- Allan Abbott

Managing the interplay between chronic pain and mental health- Amy Islip & Mat Richardson

Talking Tendons- Dr Ebonie Rio

Corinne’s Story- Corinne Nijjer

Acute pain support and nutritional and herbal medicine- Sarah McLachlan

Upcoming events for after the Covid 19 crisis

Amanda’s story- Amanda Freeman

Pelvic health-Psycho/ social considerations- Liana Johnson

Changing the relationships between perceptions & protective responses- Mat Richardson

Reference

Gifford, Aches and Pain, CNS press, 2014

Neurodynamics, History and Biases

Recently I ran a workshop for my workers and the local therapists to explore neurodynamics and their application in the clinic. At the start of the workshop I thought it was important to outline my Biases to the group. Why you ask? because my Biases will influence and guide my assessment, clinical reasoning and how I apply the technique. Knowing my biases allows me to stand back and apply more critical thinking to my clinical reasoning. My strong biases are the Biopsychosocial model of care, Neuro matrix/ Neurotag Theory and the Mature Organism Model. I have included a link below to the first part of my presentation to my workers outlining my biases. I have been guided by resources from Butler, Moseley, Coppieters and Gifford and they are great examples of clinicians that have evolve with the science and occasionally loose clinical mileage along the way. Unfortunately, I haven’t got around to reading the work of Michael Shacklock yet, who is another big name in this field of neurodynamics. This blog is a quick birds eye view of the history of neurodynamics and how theories and biases can alter our clinical reasoning of this technique.

The more modern application of the Neurodynamic technique occurred in the 1970’s-80’s with Maitland exploring variations in the slump test and Elvey with the Upper Limb Tension Tests. Coming from a Pathoanatomical/ Biomedical approach, they were searching for the source of the pain or the restriction in the nervous system. This thinking drove the notion of adverse neural tension where there was restriction along the pathways played a large role with pain and dysfunction and aggressive neural tension tests and exercises were created to try and stretch out and mobilize the tissues.

In the 80’s and early 90’s Butler further explored the role of adverse neural tension and in 1991 Butler released the book Mobilisation of the Nervous System. This was the first book I read of David Butler’s back when I was a t University 20 years ago and it stroked my biases, as I was more biomedically oriented back then. Butler wrote about the nervous system as a continuum and altering tension at one point would alter tension throughout the nervous system. Along the continuum there were points were the nervous system would become entrapped or what was called “crush” and “double crush” sites that would create adverse neural tension. The words crush could now be seen as a DIM or Nocebic language due to it creating a powerful metaphor about entrapment. David himself was not fully happy with the book as there was starting to be a shift around the world in our understanding of pain and health.

“My publisher had to wrench Mobilisation of the Nervous System away from me. I knew it wasn’t complete and I knew the pressures and forces for change in manual therapy practice were growing and uniting” (Butler, 2000)

This quote was in opening of Butler’s next book The Sensitive Nervous System, published in 2000 by Noigroup Publications. At this time there was a shift away from the biomedical model and moving to a more Biopsychosocial model of health. The two headings of Butler’s books show the shift in understanding from “Mobilisation” to one of the “Sensitive Nervous System”. The neurodynamic testing moved to explore more the sensitivity and tolerance of the organism in a particular context. In 2003 Butler and Moseley released the amazing Explain Pain. This book triggered a change in thinking for many clinicians around the world around pain and health. Explain Pain explored the emergent and contextual nature of pain and how tissue damage and pain relate poorly, and that pain was more about protection rather than indication of the state of the tissues (Butler & Moseley, 2003).

Butler teamed up with Coppieters in 2008 and explored Do Sliders slide and tensioners tension. With this shift our understanding of pain and the sensitive nervous system, it was still important to explore the mechanical effects on the peripheral nervous system and the surrounding tissues when mobilized. This is what they found:

tensioning- nervous tissue will see a lengthen effects on the peripheral nervous system of the nerve bed and change the intra neural pressures and creating a proposed pumping effect on “enhancing the dispersal of local inflammatory products in and around the nerves” (Coppieters & Butler, 2008)

longitudinal excursion- the nerve would move and glide in respects to the adjacent tissues. Example: during wrist extension the median nerve distally glide approximately 9mm.

For a lot of our patients pain is their primary concern, but it is important to educate them on the importance of movement in maintaining the health of our tissues, particularly post-surgery, immobility and when there is lots of pain related fear and disability.

The neurodynamics test are not specific to one particular tissue but are testing the sensitivity of a wide array of tissues through motion, blood vessels, fascia, lymphatic and the list goes on. The information being feed into body is just that, information. Our body will “sample, scrutinize and respond from both a cellular and an organism level” (Gifford Mature Organism Model, 2014). As clinician’s this now gives us a huge array of ways to change the relationship and context when is client is preforming neurodynamics and thus may alter their pain experience. When I am preforming these techniques with clients, I use a lot of experiential learning to show them how changing the context can alter the pain and the body can learn that is no longer as dangerous as what it once thought. Using the clients experience of a change in their pain during these techniques can be a great time to bring in some good quality education about pain. Then through graded exposure “start easy, build slowly” (Gifford 2014) you can slowly challenge the client’s relationship to pain from gentle to more aggressive contexts (movement, environmental and psychological). This graded exposure can be where you use sliders and tensioners, that can be perceived as being less aggressive to more aggressive techniques and you can alter the environment to bring in more or less danger or safety cues to the patient.

Click here for the link to the first part of the presentation on biases

Resources

Butler, Mobilsation of the Nervous System, Churchill Livingston, 1991

Butler, The Sensitive Nervous System, Noigroup Publications, 2000

Butler & Moseley, Explain Pain, Noigroup Publications, 2003

Butler, The neurodynamic Technique, Noigroup Publications, 2011

Coppieters & Butler, Do “sliders” slide and “tensioners” tension? An analysis of neurodynamic techniques and consideration in regarding their applications, Elsevier, 2008

Gifford, Aches and pains, CNS Press, 2014

Protective Zone- Watch and Act

The bush fires around Australia are devastating and my hearts go out to the communities affected. Looking at the fire warning apps on my phone I started thinking, what are the consequences if the watch and act zone remain around communities for too long: people stop going to the towns, money runs short, stress levels go up, you start moving different around your community and you become hyper vigilant. Having these watch and act zones are great short-term strategy to keep you safe and on alert, but if the watch and zone remains for too long, it can really disrupt our lives and health.

I pondered further and I started to see similarities between the watch and act zone for the bushfires and how we also protect the space that directly surrounds us. We are constantly surveying the space around us and this allows us too to interact with our environment and keeps us on the lookout for any dangers that may enter our personal space. This protective zone can be centered around a particular body part that we perceive is under threat. “The area of space that we protect aggressively will be bigger if we have a reason to protect it” (Butler & Moseley 2017). Like the fires the watch and act zone is dependent on the context, previous experience and future predictions. This watch and act zone is always changing in size depending on the context of the situation we are in.

“Our normal personal space roughly matches that area we can touch without taking a step. Its widest around our head and follows our body down to the ground. The size of your personal space changes depending on risk and practicality” (Protecting your turf, Butler & Moseley, 2017)

2 years ago, I got my finger caught in the winch rope on the front of my car and it chopped off the top of finger and I needed surgery and skin grafts. In the week that followed my protective zone around my finger became like an imaginary protective bubble centered around the finger. This protective bubble would vary in size and sensitivity depending on the context of the situations and how much danger I was perceiving around me. At the end of the first week I was walking through the school yard to drop my kids off and I found myself becoming hyperaware of every threat around me, from kids running past me, to footballs flying past me. My watch and zone around my hand increased in size and my senses were heightened, vision, smell, hearing and the sensitivity were increased and the flow of information about any potential dangers to my hand were increase. Our body will prime our immune and nervous and our senses to quickly transfer information to brain and you are constantly on alert. I was now alerted to any threat that entered the space around my hand. Instead of walking with a nice relaxed gait I was holding the arm stiff and close to my body and I was seeing a change in my movement patterns. One I left the school this protective bubble slowly over a few hours decreased in size and my senses and guarded movements slowly returned to normal. What a brilliant response of my body but let’s not let it hang around too long.

In the clinic over the years, I have seen many patients where this protective watch and act zone around their injured body part remains enlarged and sensitive for months or even years after the injury occurred. This is common sense approach if we perceive that the body part is in danger. Just moving your hand into this protective zone, you will see them tense and become hyperalert and danger detection in their body is heightened. So, how do we go about treating this in the clinic?

“top down, before bottom up” (Gifford 2014)

We need to listen to their story and identify any threats and help the patient make sense of why their body is responding the way that is. You need to build trust and a working relationship with your patient, this is called a therapeutic alliance. Gradually and slowly use graded exposure to decrease the sensitivity and size of the protective zone around the body part. Be prepared, this can be a very slow process.

“Start easy, build slowly” (Gifford 2014)

So, the next time you injury yourself or are protecting an area of your body become a curious observer and take notice of whether you develop a more sensitive or larger watch and act zone around the injured body part.

References

Butler & Moseley, Explain Pain Supercharged, Noigroup Publications, 2017

Gifford, Aches and Pains, CNS Press, 2014

Serino, Peri personal space (PPS) as a multisensory interface between the individual and the environment, defining the space of the self, neuroscience and reviews, Elsevier, 2019

Becoming who I am: Mat’s story of depression and pain

Blog #3- Becoming who I am: Mat’s story of depression and pain

I want to share my story of pain and depression from both a patient and a practitioners point of view. Pain can put a lot of strain on your finances, mental health, relationships and who you are as a person. Poor mental health and stress can be powerful predictors of the transition from acute to chronic pain. When someone comes into the clinic with persistent pain, they are not just coming in with pain, but with all the complexities that make us human. Here is my story about finding out who I am.

Mat’s Journey